Marker Text

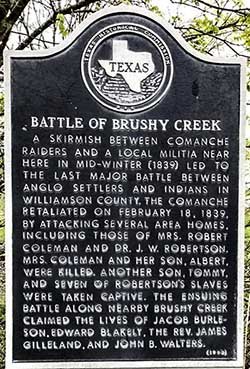

Battle of Brushy Creek - A skirmish between Comanche raiders and a local militia near here in mid-winter (1839) led to the last major battle between Anglo settlers and Indians in Williamson County. The Comanche retaliated on February 18, 1939, by attacking several area homes, including those of Mrs. Robert Coleman and Dr. J. W. Robertson. Mrs. Coleman and her son, Albert, were killed. Another son, Tommy, and seven of Robertson's slaves were taken captive. The ensuing battle along nearby Brushy Creek claimed the lives of Jacob Burleson, Edward Blakely, the Rev. James Gilleland, and John B. Walters.

Maps

Battle Of Brushy Creek Narrative By Karen R. Thompson

Much of the fiction and non-fiction history of early Texas concerns Indians and Indian fighting. The Indian stories range from romantic to brutal. During the decade of the Republic of Texas, 1836-1846, hundreds of Indian battles were fought, and one of the major and best known as the "Battle of Brushy," also referred to as the "Battle of Brushy Creek." The "Battle

of Brushy" seems to be the earlier name, and "Creek" was added later.In order to fully understand the actual Battle of Brushy, we must back up about

a week to relate the Indian problems that were occurring at the time (January 1839).Comanche Indians were seen camped on the San Gabriel River above Austin.

Their enemy, the friendly Lipans, gave the alarm to the settlers along the Colorado River. Noah Smithwick, in his book "The Evolution of a State, or Recollections of Old Texas Days; says: There were no troops in the vicinity, and knowing that if the Comanches were allowed to remain, they would soon be making predatory incursions into the settlements, we at once decided to make up a party to go against them. Colonel John H. Moore being the leading spirit in the plan was given command. Captain Eastland raised a company of thirty men at LaGrange. Bastrop raised a company of about the same number, electing me its captain. To this number was added the full fighting force of the Lipans, under the command of Chief Castro, assisted by his son, Juan Castro, young Flacco, and Juan Seis. When we reached the point at which the Lipans reported the camp, the Comanches had moved, leaving a trail leading upstream. We followed on up to the head of the San Gabriel, where we were overtaken by a storm of snow and sleet, which was so severe that we were obliged to seek shelter. We made for a grove of post oaks on the divide between the San Gabriel and Colorado, in the shelter of which we struck camp. The storm continued with increasing cold. Some of the horses froze to death, and the Indians, loth to see so much good meat go to waste, ate the flesh. Three days and nights, we remained there. In the meantime, a gun that had been set up against a tree fell down, and, being discharged by the fall, shot one of Captain Eastland's men through the body. Some of the men, discouraged by these unpropitious circumstances, wanted to turn back, but it was finally decided to move camp over to Colorado, whither the game had been driven by the storm, and there kill wild cattle, of which there were large bands, and construct a boat of the hides in which to send the wounded man down to the settlements. The storm abated on the fourth day, but the snow had obliterated the Comanches trail. We kept on up Colorado on the east side till near the mouth of the San Saba, when on ascending a rise overlooking the valley, we saw smoke

rising some miles up the San Saba. Our men had constructed a raw‑hide boat and started our wounded man down Colorado...the poor young fellow, whose name I do not now remember, died on the way down and was buried in the sand. We saddled up and started for the Comanche camp, going up within a few miles of the place, when we halted and lay on our arms while Malcolm Hornsby, Jo Martin, and two Lipans went forward after dark to locate the exact of the camp. On their return, they reported a much larger camp than the Lipans previously reported. Disconcerted by the unexpected intelligence, Colonel Moore rather demurred to attacking, but we had come out to hunt a fight and were willing to take the responsibility...We then crept upon the sleeping Indians....taken completely by surprise, the savages...scattered...Colonel Moore ordered a retreat. Quick to...take advantage of the situation, the Indians rallied and drove us back to cover a ravine...The Indians then formed in line and advanced to the attack...We drove the enemy back...They sent out a Lipan squaw, who had long been among them, with a white flag...The Comanches slipped around and got our [horses], so we were left afoot more than one hundred miles from home. Congress passed an act to indemnify us for the loss of our horses, the indemnity to be paid in commonwealth's paper, worth twenty-five cents on the dollar; so, for a $100 horse, I got $400 which I didn't allow to depreciate on my hands. [1]"Just as Colonel Moore's party were returning from their expedition against the Comanches upon the San Saba, about the eighteenth of February, 1839, citizens along the Colorado Valley, from Bastrop to Austin, were thrown into a high state of excitement by the report that the Indians had made an attack upon the settlers of Wells [Martin Wells] or Webber prairie, or perhaps both. The news is going up and down the river as rapidly as the facilities of the day would permit soon bringing together squad after squad of citizen soldiers, all eager to ascertain the cause of the alarm, which proved to be a large body of Indians

variously estimated at from two to three hundred, who had made a sudden attack upon the upper end of Well's prairie, killing Mrs. Captain Coleman and her son Albert, a lad about fifteen years old, and robbing the house of Doctor J. W. Robertson." (2)Noah Smithwick tells it this way: "The Comanches, thirsting for revenge, at once made a raid on the settlements, killing Mrs. Coleman and her son Albert and taking little five-year-old Tommy prisoner.

[3] "The Indians kept the little boy of Mrs. Coleman until he was almost grown when our men bought him

from them. He had, however, been so imbued with their ideas and habits that he went back to them, never feeling satisfied among the whites." [4]J. W. Wilbarger, in his style, further tells of the Coleman deaths in this way.

Mrs. Coleman, early in the morning, was with her family out in a small field or garden patch, which lay between the bottom timbers of Coleman branch and Colorado's bottom, when they were suddenly charged upon by a large body of Indians, who came up whooping and yelling as they emerged from their hiding places, nearby the residence. James Coleman and a man by the name of Rogers made good their retreat to Colorado's bottom, while Mrs. Coleman with the rest of the family ran towards the house, which all succeeded in gaining, but little tommie, a boy about five years old who was taken, prisoner. The attack was so sudden and the panic so complete that Mrs. Coleman did not, perhaps, think of the fate of her children until she reached the door

of her humble cabin when her mother's love induced her to look back to see what had become of them - only to receive an arrow wound exactly in the throat, from the effects of which she soon expired, but before expiring she exclaimed, "Oh, children, I am killed;" then turning to her eldest son, said: "Albert, my son, I am dying, get the guns and defend your sisters." Albert, a mere lad about fifteen years of age, and his little sisters were the only persons left to defend the house and their already murdered mother from further injuries from the inhumane, brutal savages.Young Albert fought with heroic bravery for a while, killing and wounding some three or four of the enemy; but finally, he received a wound which in a very short time proved fatal, and he breathed his last with his head pillowed in the lap of his oldest sister, the last words he uttered being, "Sister, I can't do any more for you. Farewell."

This left his two little sisters to take care of themselves as best they could. The little girls, who had taken refuge under the bed after the death of their brother, kept up a conversation with each other, as they had been told to do, which doubtless deterred the Indians from entering the house, thereby saving their lives and the house from being plundered. “The Indians now began to withdraw, halting at the house of Doctor J. W. Robertson, robbing it of its contents, ripping

open the feather beds in the open air, thus giving the country around a very singular appearance, and carrying off captive seven of the Doctor's negroes."About noon, the citizens from above, twenty-five in number, had collected and, electing Jacob Burleson, their captain, began immediately to inspect, and some two hours later, they were joined by twenty-seven men under the leadership of Captain James Rogers, from Below, brother-in-law of Captain Burleson, making in all fifty-two men. So eager were the men for the chase that they concluded not to go into any further election of officers but to march in double file and for Rogers and Burleson to ride each at the head of one file and command the same. "About ten o'clock the next day," says Mr. Adkisson, who was present and participated in the battle, "we descended

a long prairie slope leading down to a dry run, a little above and opposite Post-Oak Island, and when about three miles north of Brushy, we came in sight of the enemy."On the run, and directly north and in front of us, was a thicket, and the enemy, when first discovered , was about one-half mile above, and to the west of the thicket, bearing down towards the same, and as we thought, with the intention of taking possession of and giving us battle from it.

We immediately agreed to charge up, open file, flanking to the right and left, cutting Indiana off from, we taking possession of, the thicket ourselves. The larger portion of the enemy is on foot, and we all well mounted. We could and ought to have taken possession of the thicket and would have done so but for the flinching of a few men, which threw the whole command into a state of confusion, resulting in the death of Captain Burleson and our inglorious flight from the field

, leaving his remains to the mercy of the enemy. There were those of us who dismounted and hitched our horses as often as three times but at last, had to retreat, and in doing so, the horse of W. W. Wallace became frightened, pulled away from him, and ran among the Indians, leaving the gallant Texan on foot in the midst of conflict. His horse was soon mounted by one of the Indian warriors, who appropriated him for his own use. Just at this time, Captain Jack Hayne, observing the perilous situation of Wallace, made a dash for him, pulled him up behind him on a horse, and both made good their retreat.The whole command fell back to Brushy (the Indians making no attempt to follow us) in a line one mile in length; the main body of us mortified at the result of the mornings' conflict, unwilling and ashamed to return to the settlements without a fight, and being loath to leave the dead body of the gallant Captain [Burleson] upon the field, we halted at Brushy, not knowing what to do.

But while halted here in a state of indecision, General Ed. Burleson, who had heard of the raid made by the Indians, raised thirty-two men, followed our trail, halted, and brought back those of our men who had so precipitately fled in the morning. This reinforcement swelled our number to eighty-four men, with General Edward Burleson in command, assisted by Captain Jessie Billingsley, who had distinguished himself at the battle of San Jacinto. After a general consultation and exchange of opinions, the whole command moved on sorrowfully yet determined to retrieve the fortunes of the morning. About two o'clock p.m., we struck the enemy, but not where we expected to find them. Instead of occupying the thicket, they had selected a very stronghold in the shape of a horseshoe, with the very high and rising ground at the toe -the direction we would approach them unless we changed base, which, after reconnoitering for a while and exchanging a few shots we did, dropping down, crossing the run and dividing our command, one party under the command of Captain Billingsley, taking possession of the run below the Indians, while the party went above and gained possession of a small ravine which emptied into the main one just above the Indians. Our intention is to work our way down and drive the enemy before us, while Captain Billingsley was to work his way up the ravine, thus securing a complete rout of the Indians. But nature and fortune seemed to favor the enemy; the ravines leading from each of our little commands to where the enemy lay massed behind high banks on either side, spread out into an open plot forty or fifty yards before reaching him, which would have made it extremely dangerous for us to carry out our plans. Thus failing in our attempt to route and chastise the enemy and recapture the prisoners they held in possession, we were forced to select safe positions, watch our opportunities, and whenever an Indian showed himself, to draw down on him and send the messenger of death to dispatch him. In this manner, the fight lasted until sundown, the Indians retreating under cover of night and leaving us in possession of the field, putting up the most distressing cries and bitter lamentations ever uttered by mortal lips or heard by mortal ears. We camped on the battlefield that night, and early next morning, the sad duty devolved upon us to make litters to convey our dead and dying to

the settlements. How many Indians were killed, we have no means of knowing. Their bitter wails indicated that their loss was great, either in quantity or quality, perhaps both. We lost during the day four of our best and most prominent citizens, to wit: Jacob Burleson, Edward Blakey, John B. Walters, and Rev. James Gilleland. The last-named lived some ten days after receiving his wound. I have been thus particular in mentioning the names of those who fell in the day's conflict, that their names may be enrolled high up in the temple of Texas liberty, and find a niche in the hearts of an appreciative people.” [5]The two Indian encounters, Colonel Moore and Company in San Saba and Mrs. Coleman's murder near Bastrop, had led up to the ill-fated Battle of Brushy where "four of the best men on the frontier, were killed [Burleson, Walters, Blakey , and Gilleland.

[6]About noon on Monday, February 24, 1839,* immediately following the murder of Mrs. Coleman and her son Albert, twenty-five citizens of Wells Fortga

gathered to pursue the Indians. They elected Jacob Burleson) brother of General Edward Burleson as their captain. General Ed Burleson, in his report to Albert Sidney Johnston, Secretary of War for the Republic of Texas, gave this report:"On Monday...[February 24, 1839] they [Indians] attacked the house of widow Coleman, 12 miles above Bastrop...A party fired at Mrs. Coleman, who was at work in the garden fifty paces distant from the house, and slightly wounded her neck with an arrow; she fled with all speed for the house and succeeded in reaching it; at the time of her entering the house, where was in the room her eldest son, about 12 years old, and three other small children...The boy and Mrs. Coleman were killed...A party of fifty men from above Bastrop went immediately in pursuit and overtook them 25 miles north of the Colorado, where a skirmish took place - the Indians having the advantage of position, caused the whites to fall back about three miles, with the loss of one man, at which place I fell in with them with thirty men, when I immediately went in pursuit and overtook them; in the meantime, the Indians have changed their ground for a more advantageous position, on discovering me, they took a

stand; I attacked them at about one o'clock, p.m. - I continued to pick them off at every opportunity until dark; they retreated from their stronghold under cover of night and, from their superior numbers, were enabled to carry off their dead and wounded, as appears * dates vary, but this date appears to be the most correct from the statements of the negro who was found on the battleground after night, with nine arrows shot into him, supposed to have been left for dead. * He says he saw several killed and wounded, say thirty from the appearance of the blood seen on the ground. I am inclined to believe the above number is not overrated. Our loss in the last attack was two killed and one wounded, who has since died." [7]John Holland Jenkins, in his book, gives this version.

After the murder of Mrs. Coleman and her son Albert, "soon forty or fifty men under the command of Jacob Burleson, brother of Edward, were on the trail of the savages, which they had no trouble following. The Indians were evidently not afraid and made no effort to conceal their whereabouts, doubtless feeling

confident in their own strength.Burleson's forces overtook them at Brushy Creek .

Dismounting, he attacked them immediately. The Indians then charged, and Burleson

ordered a retreat. Coming right on, the savages were very near overrunning some of our men before they could reach their horses. Jacob Burleson, another brother of Edward Burleson, was killed, but no one else was hurt. [Jenkins had first stated that the Burleson killed was Jonathan] On their return march, when they buried Burleson, they found that the savages had cut out his heart. Thus another of our bravest men was sacrificed.About four miles back on the retreat, they met General Edward Burleson with reinforcements and at once turned for a fresh charge.

In the meantime, the Indians had secured a fine position in a hollow and could not be drawn from cover. Some of them were well-armed and fine sharpshooters. The fight continued until dark and might be termed a drawn * I think this was probably one of Dr. Robertson's negroes battles, but during the night, the Indians retreated. Ed Blakey, John Walters, and Parson [James] Gilleland, three more of our best citizens, were killed here, leaving dependent and defenseless families. In the meantime, William Hancock had charge of a small squad of recruits, to which I belonged; we were just behind Burleson's force and were making all possible speed to overtake them...Finally, after a short deliberation, deciding it to be dangerous

for so small a party to be riding about in the face of such odds, we returned to the settlements." *The following information is given in the footnotes in Jenkins's book.

In describing the Battle of Brushy, "All of the Burleson brothers, Edward, Jacob, John, Jonathan, and Aaron were in this fight; hence the confusion. Captain Jacob Burleson ordered his men to dismount and charge the Indians. He, Winslow Turner, and Samuel Highsmith did so, but as there were only twelve men in the whole group, the other nine deemed the chances too great and turned and fled, leaving their comrades to face the Indians. Seeing the rest of the men deserting, Captain Burleson and the other two fired and started to mount, but one, a boy about fourteen years old, jumped on his horse without untying him. The captain ran back and untied the boy's horse but was shot in the back

of the head when he started to remount. The savages, thinking that he was General Edward Burleson, the Texan they hated most, cut off his right hand and right foot, took out his heart, and scalped him. * Jenkins was not at the Battle of Brushy, and that probably accounts for some of his mistakes. He gives the date as 1839, but one of his references for that is Wilbarger, Indian Depredations in Texas, and Wilbarger gives 1838.Jacob Burleson had come to Texas in 1832 with his brother John.

He served in the Texas Revolution from February 28 to June 1, 1836. He settled on his league

and labor of land in Burleson County, where his wife Elizabeth and their five children lived after his death.In 1848 when Williamson County was formed, the area where the Battle of Brushy took place became part of the county.

The battle was a "running battle," so it does cover a wide area. From the description of the area where General Burleson's troops fought, "ravines...behind high banks on the other side" [page 8], it fits the area just south of Taylor where the school children erected a red granite monument in The area is located 1.4 miles south of the Taylor city limits on Highway 95, on the west side of the road. The monument is on private property, set back from County Road 452. The

graves of the four men killed have not been located. The creek where the Battle of Brushy Monument is located is known by two names, Battleground or Cottonwood. The battle also was around Boggy Creek. The Taylor Daily Press, in an article "Marker, Recalls Battle of Brushy," June 27, 1986, states." The battle was fought in 1839, only three years after Texas gained independence from Mexico. It is said to have been the last tragic encounter with Indians in Texas. While the encounter is called the Battle of Brushy, it culminated north of that stream and is reported to have been its fiercest along the creek now known by two names, Battleground and/or Cottonwood. Mahon Carry, whose grandfather was a very young man at the time of the battle, says it was a running fight along the banks of the stream, according to handed down family accounts. He questions that the marker is on the exact spot but thinks it is in the area. Stories say that a number of Indian bodies were later discovered in Boggy Creek, only a short distance south of Battleground Creek. The monument was dedicated on November 5, 1925

, with the Taylor High School Band providing the music for the occasion, and with Dr. Walter Prescott Webb, a famed history professor at the University of Texas, as a speaker, according to notes of former Taylor Superintendent T. H. Johnson has in his records...the red granite marker was erected by the school children of Taylor."

from the "Indian Depredations In Texas" book by J

. W. Wilbarger 1889

Indian wars in Central

Texas

The Battle

of Brushy

Just as Colonel Moore's party were returning from their expedition against the Comanche upon the San Saba, about the eighteenth of February, 1839, citizens along the Colorado valley, from Bastrop to Austin, were thrown into a high state of excitement by the report that the Indians had made an attack upon the settlers of Well's, or Webber prairie, or, perhaps, both. The news is going up and down the river as rapidly as the facilities of the day would permit, soon bringing together squad after squad of citizen soldiers, all eager to ascertain the cause of the alarm, which proved to be a large body of Indians variously estimated at the front two to three hundred, who had made a sudden attack upon the upper end of Well's prairie, killing Mrs. Captain Coleman and her son Albert, a lad about fifteen years old, and robbing the house of Doctor J. W. Robertson, who, at the time, happened to be on a visit with his family at the residence of his neighbor and brother-in-law, Colonel Henry Jones. Mrs. Coleman, early in the morning, was with her family out in a small field or garden patch, which lay between the bottom timbers of Coleman branch and Colorado's bottom, when they were suddenly charged upon by a large body of Indians, who came up whooping and yelling as they emerged from their hiding places, nearby the residence. James Coleman and a man by the name of Rogers made good their retreat to Colorado's bottom, while Mrs. Coleman with the rest of the family ran towards the house, which all

succeeded in gaining, but little Tommie, a boy about five years. Old, who was taken, prisoner. The attack was so sudden and the panic so complete that Mrs. Coleman did not, perhaps, think of the fate of her children until she reached the door of her humble cabin when her mother's love induced her to look back to see what had become of them only to receive an arrow wound exactly in the throat, from the effects of which she soon expired, but before expiring she exclaimed, "Oh, children, I am killed;" then turning to her eldest son, said: "Albert, my son, I am dying, get the guns and defend your sisters." Albert, a mere lad about fifteen years of age, and his little sisters were the only persons left to defend the house and their already murdered mother from further injuries from the inhumane, brutal savages.Young Albert fought with heroic bravery for a while, killing and wounding some three or four of the enemy. Still, finally, he received a wound which in a very short time proved fatal, and he breathed his last with his head pillowed in the lap of his oldest sister, the last words he uttered being, "Sister, I can't do any more for you. Farewell."

This left his two little sisters to take care of themselves as best they could. The little girls, who had taken refuge under the bed, after the death of their brother, kept up a conversation with each other, as they had been told to

do, which doubtless deterred the Indians from entering the house, thereby saving their lives and the house from being plundered.The Indians now began to withdraw, halting at the house of Doctor J. W. Robertson, robbing it of its contents, ripping open the feather beds in the open air, thus giving the country around a very singular appearance, and carrying

off captive seven of the Doctor's negroes.About noon the citizens from above, twenty-five in number, had collected and, electing Jacob Burleson their captain, began immediately to inspect, and some two hours later, they were joined by twenty-seven men under the leadership of Captain James Rogers , from below, brother-in-law of Captain Burleson, making in all fifty-two men.

So eager were the men for the chase that they concluded not to go into any further election of officers but to march in double file and for Rogers and Burleson to

ride each at the head of one file and command the same. "About ten o'clock the next day," says Mr. Adkisson, who was present and participated in the battle, "we descended a long prairie slope leading down to a dry run, a little above and opposite Post-Oak Island, and when about three miles north of Brushy, we came in sight of the enemy."On the run, and directly north and in front of us, was a thicket, and the enemy, when first discovered, was about one-half mile above, and to the west of the thicket, bearing down towards the same, and as we thought, with the intention of taking possession of and giving us battle from it.

We immediately agreed to charge up, open file, flanking to the right and left, cutting the Indians off from, and we taking possession of, the thicket ourselves. The larger portion of the enemy is on foot, and we all well mounted, we could, and ought to have, taken possession of the thicket and would have done so but for the flinching of a few men, which threw the whole command into a state of confusion, resulting in the death of Captain Burleson and our inglorious flight from the field, leaving his remains to the mercy of the enemy

. There were those of us who dismounted and hitched our horses as often as three times but, at last, had to retreat, and in doing so, the horse of W. W. Wallace became frightened, pulled away from him, and ran among the Indians, leaving the gallant Texan on foot amid the conflict. His horse was soon mounted by one of the Indian warriors, who appropriated him for his own use. Just at this time, Captain Jack Haynie, observing the perilous situation of Wallace, made a dash for him, pulled him up behind him on his horse, and both made good their retreat.[NOTE.—For

the rescue of Wallace by Captain Haynie, the latter was presented with an elegant rifle, handsomely mounted, by the father of Wallace, who was then living in Tennessee. Owing to the handsome appearance of this rifle, it will be remembered by many old Texans. William Wallace is the father of John Wallace of Travis county.]The whole command fell back to Brushy (the Indians making no attempt to follow us), in a line one mile in length; the main body of us mortified at the result of the morning's conflict, unwilling and ashamed to return to the settlements without a fight, and being- loath to leave the dead body of the gallant Captain up, m the field, we halted at Brushy, not knowing what to do.

But while halted here in a state of indecision, General Ed. Burleson, who had heard of the raid made by the Indians, raised thirty-two men, followed our trail, halted, and brought back those of our men who had so precipitately fled in the morning. This reinforcement swelled our number to eighty-four men, with General Edward Burleson in command, assisted by Captain Jessie Billingsley, who had distinguished himself at the battle of San Jacinto. After a general consultation and exchange of opinions, the whole command moved on sorrowfully yet determined to retrieve the fortunes of the morning. About two o'clock PM, we struck the enemy, but not where we expected to find them. Instead of occupying the thicket, they had selected a very stronghold in the shape of a horseshoe, with the very high and rising ground at the toe—the direction we would approach them unless we changed base, which, after reconnoitering for a while and exchanging a few shots we did, dropping down, crossing the run and dividing our command, one party under the command of Captain Billingsley, taking possession of the run below the Indians, while the other party went above and gained possession of a small ravine which emptied into the main one just above the Indians. Our intention being to work our way down and drive the enemy before us, while Captain Billingsley was to work

his way up the ravine, thus securing a complete rout of the Indians.But nature and fortune seemed to favor the enemy; the ravines leading from each of our little commands to where the enemy lay massed behind high banks on either side spread out into an open plot forty or fifty yards before reaching him, which would have made it extremely dangerous for us to carry out our plans.

Thus failing in our attempt to route and chastise the enemy and recapture the prisoners they held in possession, we were forced to select safe positions, watch our opportunities, and whenever an Indian showed himself, to draw down on him and send the messenger of death to dispatch him. In this manner, the fight lasted until sundown, the Indians retreating under cover of night and leaving us in possession of the field, putting up the most distressing cries and bitter lamentations ever uttered by mortal lips or heard by mortal ears. We camped on the battlefield that night, and early next morning, the sad duty devolved upon us to make litters to convey our dead and dying to the settlements. How many Indians were killed, we have no means of knowing. Their bitter wails indicated that their loss was great, either in quantity or quality, perhaps both. We lost during the day four of our best and most prominent citizens, to wit: Jacob Burleson, Edward Blakey, John Walters, and Rev. James Gilleland. The last-named lived some ten days after

receiving his wound. I have been thus particular in mentioning the names of those who fell in the day's conflict, that their names may be enrolled high up in the temple of Texas liberty, and find a niche in the hearts of an appreciative people. FOR NO SLAB OF PALLID MARBLE

,

WITH

A WHITE AND GHASTLY HEAD,

TELLS THE WANDERERS

IN OUR VALE,

THE VIRTUES OF OUR DEAD

.

THE WILDFLOWERS LIE ON

THEIR TOMBSTONE,

AND DEWDROPS PURE AND BRIGHT

,

THEIR EPITAPH,

THE ANGELS WROTE

IN THE STILLNESS OF THE NIGHT.